Reflections on Resistance from Santiago, Chile

from the perspective of Bangladeshi- American Berkeley Grad

SEPT. 03 . 2025

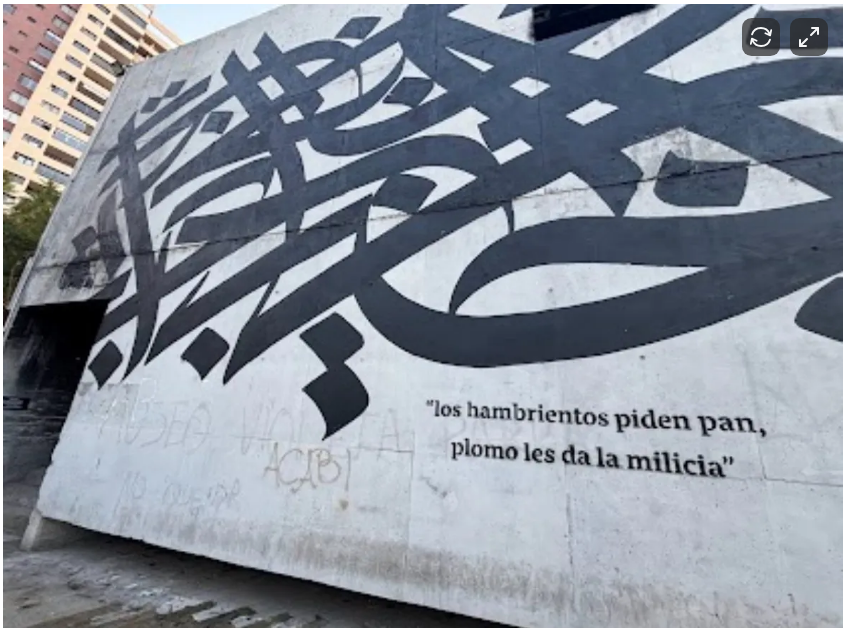

It was mid-June and I was standing in a museum in central Santiago, alone for a few hours before meeting a friend from college who was studying abroad in the South American city. The Museo Violeta Parra had once been a space dedicated to the work of the renowned Chilean artist Violeta del Carmen Parra Sandoval. In 2019, the building was burned down in a mass public display of anger amidst a youth-led social uprising and anti-regime protests.

Now, six years later, what remains of the building has been slowly rehabilitated by a community-led group of activists and artists.

The first exhibit they chose to use the still-blackened and crumbling concrete walls of the museum for was a curated feature of the work of Palestinian photographer Belal Khaled.

When I arrived that day, a keffiyeh-wearing docent in her 20s showed me around the rooms. Translated poems and plaques in Spanish for me. I stood alone after and took in the atmosphere of that room in silence. The photos were ones I had seen on timelines and in articles before—each post and click was someone behind a screen desperately hoping that the anguish would reach those with the power to stop it all. In that room, those photos took on a different meaning, set intentionally against the backdrop of burned-down beams, black ash-stained exposed ceilings and a chilling, somber quiet.

The Chilean docent stood behind me, asked if I wanted to meet the people working in the community garden downstairs. I followed her, thinking to myself about the others in Chile and around the world like her. In places thousands of miles from Gaza and its near two years of mass televised genocide, who take time from their lives and their day to build places like this. Who write, lead, and speak so that this tragedy does not go ever for a moment unseen.

I was a college student at UC Berkeley when student protests broke out across the nation. I remember so well the students who inspired me, who sat in tents for weeks with me, organized actions and spoke with precise articulation.

The roommate who, on the day she graduated, ended up photographed in her cap and gown in the New York Times, holding up a letter calling for the school to divest.

As a Bangladeshi, I think often too of our recent student-led uprising. This past August marks a year since university students withstood mass police violence and led a movement that unseated a ruthless sixteen-year dictator everyone had grown complacent to- until the dire job market and oppressive crackdown on dissent became too much for a generation that longed for something better.

I think of the Bengali model & artist I met two summers ago at an art market in Dhaka. Seeing a picture with him on my timeline during those August protests of 2024—he’s yelling, drenched in rain and blood, long hair pushed back and holding hard onto the hands of students being shot on the street.

The caption in Bangla read “33 July,” a reference to the endless, bloody July that ended finally five days later, with widespread anger coalescing into a single demand: the resignation of Sheikh Hasina. Watching that summer from overseas the days of unimaginable massacre and that day in August when a mob of literal millions walked to her door.

The jubilation that took those streets in the hours after. My grandmother’s joy—“I gave those kids sticks and bricks!” she said on the phone with me that day. “They did it, they did it.” She was almost crying then, so overcome with pride. The murals that took over the city in the aftermath, students splashing walls with slogans and color. Their bravery and sacrifice succeeded in convincing Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, to put aside his reluctance and honor their request to lead the interim government that stands still today with a country eager to see change.

In recent years, as much as I have been inspired by those on our screens and around me, there have been moments when my peers and I asked questions of our community and ourselves. What could each of us do more of to answer the call that this moment in history was making? As a student at Berkeley and in a semester in D.C, we all made daily decisions on the extent of capacity we had for active engagement and leadership dedicated to documenting the Gaza genocide, and our complicity as American taxpayers.

Yet my role models who continuously inspire me and shaped my views on what political action looks like have always included my family—particularly the men across generations. My grandfather in the ’70s who pooled Bangladeshi doctors against a genocidal regime. My engineering student father, who risked his visa and immediately put together a press conference in Minneapolis the day after 9/11 to connect mainstream media to the voices of Muslim students. My data analyst uncle, who left literal fame behind as the drummer of an adored band to support a boycott of a music festival tied to Israeli defense funding. They, who understood that even with rigorous study and a non-humanities career, political principle demands something of them too.

My parents and their peers who grew up in midwestern cities quoting Malcolm X , now teach their children to never let go for an instant our right to equality and justice. The leaders who taught us that to question this country’s direction and decisions comes from not a place of hate but of genuine care for the people and the community we live among. That to self-isolate, resign ourselves to complacency and refuse to build coalition means we gave up our right as an American citizen and a skilled member of this country already.

Like the years that followed 9/11, with the rise of pervasive profiling, the establishment of the Patriot Act and the entity of ICE, these last two years and the years following are highly consequential—not just for our own faith community pained by an enduring genocide, but for those all around us affected by current aggressive crackdowns on protests and free speech.

If students and a generation in Chile can continue the spirit of an uprising six years prior by choosing to honor and center Palestine today, we as Americans and Muslim- Americans like myself can continue to as well, in the way our lives and skills empower us to do so. If you are an artist, continue painting and posting. If you are a writer, continue to document and bear witness to the genocide. Use your unique talent and intelligence thoughtfully and wherever you work or donate your time, ask questions. Examine connections. Build coalitions. Speak out. Be intentional with your skills, your voice, and your labor.

That is the power each of us holds—and it’s what this moment in history is asking of us all.