What 4 days, 43 miles and 4,650 meters above

sea level taught me

Or how one avid hiker nearly passed out on the Salkantay trek in Peru, attempted with some success to find the meaning to life's next choices and cried in front of a wonder of the world

NOV . 02 . 2025

In my twenty one years I’ve always searched for something that takes me out of my head, forces that dissociative background noise away and allows me to see and truly feel the world as it is in front of me, it’s wind on my skin. To look around present and open eyed and understand the singularity of the moment in my hands.

I’ve found it in moments here and there, among friends at my college campus, at milestones moments, in cars with open windows, the California coast and shared playlists with loud guitar riffs.

Yet it was this summer, alone traveling after my college graduation in South America I found what I was looking for finally in full on a 43 mile four day trek through the Salkantay Mountain pass to a wonder of the world, Macchu Picchu.

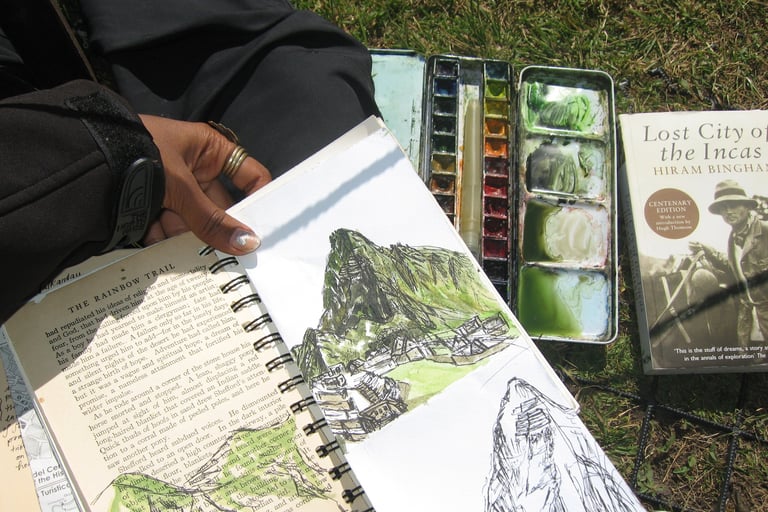

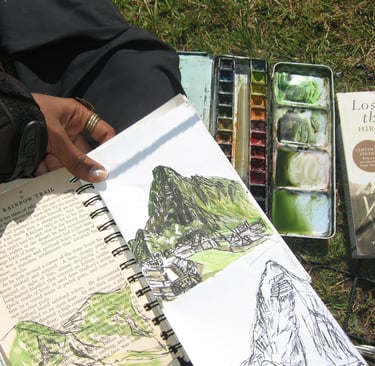

Hiram Bingham, the American academic who publicized the existence of the site to the world through his account of his expedition in 1911 writes in his book The Lost City of the Incas; “ Those snow-capped peaks in an unknown and unexplored part of Peru fascinated me greatly. They tempted me to go and see what lay beyond. In the ever famous words of Rudyard Kipling there was ‘Something hidden! Go and find it! Go and look beyond the ranges-Something lost behind the ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!’

Those ranges and that route are no longer lost or unknown — in fact 30,000 hikers a year pass through the trails that lead through the Salkantay pass to Macchu Pichu. I was one of hundreds that week, taking on a hike we’d all probably only do once in our lifetimes. Una vez en la vida.

It was the last week of July, my four weeks at a Spanish immersion school in the historical San Blas district of Cusco has ended and I was set for a 4 am start to a trek I felt barely prepared for. Taking my handful of experiences camping and backpacking in California, I assumed I needed more than what I really did. For much of the days after, I silently cursed my over-preparedness as the weight proved exhausting on the high altitude trails. The four weeks of school and time living in Cusco made me comfortable striking up conversations with my group and the guide, yet I was still still thrown off by the heavy overrepresentation of Americans and Europeans, mainly French and German in these travel spaces. I found their comments about locals and their comparisons they made to their countries off-putting, but recognized that my presence in these groups was a privileged perspective in itself. In college I had been closely involved in a students of color centered outdoor recreational club, and over the years had nearly forgotten that many much of hiking and trekking tourism around the world was remarkably less diverse.

The school had been a great space however to find friends both international and Peruvian. Many of the friendships I made were fast, intense and taught me perspectives I will always remember. I bonded with others over shared identity and in many cases unexpected similarity. The 29 year old singer with bright puffer jackets, bold eyeliner and even bolder outlook on life who took me under her wing for those weeks. I see my younger self in you , she said. A week prior to the Salkantay we rambled and ranted together for hours on a day hike through the Seven Lakes of Ausangate, the turquoise blue and red streaks of those lakes and jaw dropping mountain landscapes. I struggled with the altitude and thin air there, fear creeping in about how I’d handle the next week’s trek. Found myself falling behind her, hands on my knees barely able to breath. She was ahead, somehow singing and so high on life (and her incredible lung stamina). At one point she started belting that one song from Mulan, and we started to laugh. She brandished her hiking stick at me, her braids and bright orange jacket glinting in the harsh sun , “Be a man! you must be swift as the the coursing river, mysterious as the dark side of the moon! ”. By the time we reached the peak of the hike, we were out of breath and laughing about perhaps discovering the secret to life : embracing the mindset of a white man. I realized I felt I had literally died and only she had brought me back to life. When we said goodbye later, I gave her a small painting of her and that mountain. “You always meet people twice” she said, “ don’t worry” .

A week later, I was alone this time on the trek, struggling again with the altitude in a way I had never expected. I fell behind frequently, stopped out of dizziness too many times, felt like giving up and watched horses pass me by wondering if I was supposed to be on one. I accepted my slow pace and allowed myself some grace instead — so what if you’re slow, you came this far for a reason. You wanted to do this, to prove to yourself you were capable of it. Thoughts tumbled forward from my mind alone and silent on those trails, things I had not thought about in months. The existential questions of your 20s after college graduation, the lingering left-over questions of relationships, what am I doing next? Or better yet, who am I after this? What can I carry from here to my life at home, or will it all just disappear into the air?

I wanted to journal, to paint and sit on rocks and just think. There was no time for it really, the trek rigorously continued and I needed to keep up. Lake Humantay’s grandeur and the first night passed by in a blur.

When we reached the peak of the Salkantay pass on the second day, I barely made it in time to join the group reflecting in a circle at the top. 4650 meters above sea level, a wooden sign read. They gathered around a rock tower on the ground, scattered coca leaves and spirits from a cup. I’d been reading “ The Hold Life Has” by anthropologist Catherine J. Allen who journeyed throughout Peru’s towns in the 80s, interviewing Runa or indigenous Andeans who spoke Quechua, blended inherited Incan traditions with Catholicism and centered significant rituals around the sacred coca leaf.

“A chewer simply whispers under his breath while blowing the leaves, without calling attention to the words. The invocation provides a way to confide anxieties without having to admit them directly.”

The Humantay and Salktanay mountains are partner spirits or Apus, I read. The Salkantay seen in Andean cosmology and Quechua culture as a spirit of strength and a healing doctor, while the Humantay peak is seen as the serene and protective “head” of the Valley.

So make a prayer, what ails you?

I’d been holding onto a tasbeeh or string of wooden prayer beads during the trail, finding dhikr or the practice of Islamic repetitive remembrance suited hiking well. Accompanied that feeling of your breath being taken away by the beauty God created, an experience I was incredibly grateful to bear witness to.

What to pray for, was a question I thought about the entire trip. Strength in myself, in my identity, in who I am without school or a position— knowing that neither are ever guaranteed forever. Safety and joy for my family and friends. Justice for the thousands killed under the watch of a thousand cameras the past two years.

Along the trail, I made just a couple genuine connections with others. The difficulty of it made it incredibly hard to talk along the way, but there were conversations in rest stops and during meals I remember. The Singaporean girl who shared in my feeling of isolation and alienation among the packs of European travelers. The Coloradan who though fast and far ahead of us all, looped back to make sure I was never left alone. Their story was interesting; quit after years of depression in financial analysis, sold their home and with the privilege that the means gave them, became fully nomadic. They were heading home briefly after this trek to attend the unexpected funeral of a close friend. Later they wrote a note in my journal I’ll always remember.

That final fourth day came fast. The final push, I had stupidly not slept at all the night before, staring stuck in thought at the stars all night. A few of us were on a constrained timeline due to our entrance ticket and separated from the larger group, we were given only a hastily drawn map of the train tracks we were to follow for hours until we reached Aguas Calientes, the pueblo town that marked the entrance to Macchu Picchu. Am I in a video game? I thought to myself. There’s no way our only directions right now is a sketch on a torn out piece of notebook paper.

Walking along the Hydroelectrica train track, cutting into the Andean jungle and across grafitti covered bridges, I felt out of my body, delirious and incredibly sleep deprived. I passed through a tunnel. My group was far ahead of me. It was almost sunset. Late afternoon sun pierced through and illuminated a girl with light brown hair and a periwinkle blue bandana. Carrying a stem of purple mountain flowers, she passed through my exhausted, fever-dream fog, and her voice floated to me—lilting and magical. That way to Machu Picchu, she pointed the flower through the tunnel, smiled at me and kept walking. You’re beautiful, I tell her as she passed. Maybe she was a spirit, something about that moment did not feel real. We neared the town of Agua Calientes, the sun setting against the triangle face mountains. a train whistle cuts through announcing it’s pass through the forest. I stand watch it rush past me and feel its wind in my hair. I’m tired, sweat drenched and nearly at my complete collapse, but incredibly alive. In my delirium, I start the hear the opening notes of Joe Hisashi’s The Sixth Station as I look around. The landscape with its overgrown jungle covered tunnels, train tracks and glowing lanterns at empty food stalls reminds me of the portal between the real and spirit worlds.

The last hours of the trek were so intense that I knew I needed to record it as quickly as possible and wrote a stream of consciousness entry in my journal that night.

Arriving in the city, my eyes blurred all the bright lights of all the shops lining the tight uphill pathways lining the river. I was still hearing that song in my head, felt as if I was at the bathhouse perhaps. Getting to the hostel for a night of rest before my 6 am entrance to the historical site, I sat on the floor, thinking of all the beauty I had seen over the past days. Called a family member, “I’ve been spirited away I think” .

The next morning, I entered the site in the dark before dawn. I hadn’t given much thought to Macchu Picchu itself while on the trek, was instead caught up with the passing mountain peaks and valleys. But on that morning, I understood why millions every year came there.

The sun rose, burst through the mountain’s gate to our right. Hit the ruins and the green covered Waynupichu mountain behind it in dramatic rays, a surreal chilling moment I’ll always remember. I stood there in shock.

ah so this is why this place is famous.

Voices faded away and everything slowed. I sat on the mountain overlook there for hours, took out my sketchbook and didn’t move. In the third hour I started to cry. Finally. I struggle to cry when it’s needed I find, often letting things bottled up overwhelm me until when I’m alone or surrounded by strangers. Strangely trains or planes have seen me cry, in middle seats and by windows surrounded by 200 people I don’t know. And now, I suppose Machu Picchu. I want to sink into the ground and grass here and die maybe here i thought to myself, let time pass. Wanted all of the world except for this to fade away. For everyone, the internet, cities and the clock ticking to not exist to me. I’d like to be a stone here, a blade of grass maybe. It likely was the exhaustion of the trek speaking, but I’ve never wanted so much to stay solitary, silent and simply present somewhere the way I felt in that morning there.

Like that week before, sitting and feeling small in front of the peaks of Ausungate, that little girl inside sat there and cried and cried. I didn’t deserve that! The things that happened to me, what they said or what they left me with. But it happened any way, and revealed ways I’d been naive. To now accept that it is what it is, faith in the knowledge that pain will pass and move on with the lesson of what to look carefully for the next time.

I sketched an outline of the hills. It’ll pass, I wrote over and over.

In my last twenty minutes at the site, I noticed a family sitting near me and struck up a conversation with the mother who like me, was born in Minnesota and reminded me strangely of a past elementary school teacher. “I traveled a lot in my 20s, found myself in towns in Morocco and Jordan not frequented by crowds of tourists. Those places, people and few days have always stuck with me” Go find a town like that, she urged me after listening to how much I loved my time in Peru but felt like something was still missing before I could go home.

So in my last few days in the continent before my flight home, I did. Scared my parents a bit and decided that with the confidence a month in the country and the trek had given me, I could navigate an overnight Peruvian bus system meant for Lima citydwellers on weekend getaways and spent three days in Oxapampa, a small town at the lower edge of the Andean cloud forests and the Parque Yanachaga Chemillen. Journaled, sat alone in small restaurants, met local families and slowed down to my heart’s content there.

How did this American find this? I got asked frequently. Shoutout to ChatGPT, that conversation at Macchu Picchu and some newfound confidence.